In the literature on product management, much revolves around growth, new features, and the next big bet. Yet there is an equally important, but often neglected question: When is the right time to intentionally sunset a product?

That moment often determines whether a company wastes resources or creates space for something new.

In this blog post, I want to explore:

- why product managers often struggle to recognize when a product should be shut down,

- which mindset helps to face this uncomfortable question honestly,

- and how a structured process can support product managers in making a clear assessment of their product.

Why it’s so hard for product managers to decide to sunset a product

There are essentially four reasons why this decision is so difficult:

- Fears

- Biases

- The environment

- The complexity of the decision

Let’s take a closer look at each.

Fears

The very topic of this blog post might already trigger emotions in some product managers. Two fears in particular stand out:

Fear for one’s own career: Companies typically hire product managers and assign them a single product. That product becomes part of their professional identity. In introductions, you might hear: “Hi, I’m Basti, Product Manager for the mobile app.” A career becomes closely tied to the success of the product.

It’s therefore understandable that a product manager fears shutting down the very product with which they’ve built such a strong sense of shared destiny.

Fear for the careers of team members: Product managers often lead cross-functional teams of software engineers, UX designers, QA specialists, and more. Ending a product inevitably raises questions about the future of these colleagues. People who may have worked overtime, even weekends, to meet deadlines. The decision affects more than just the PM themselves.

And even when jobs aren’t directly at risk, strong bonds within the team can make it tempting to postpone a tough decision simply because things are currently going well.

Both fears make it difficult to look at the situation objectively.

Biases

A cognitive bias is a distortion in perception. Many are well researched. Here are three that are especially relevant:

Sunk Cost Fallacy: We tend to keep investing in failing initiatives when we’ve already sunk significant time, money, or reputation into them.

Confirmation Bias: We selectively perceive only the data that confirms our existing beliefs – for instance, that our product is still a good investment.

Self-Serving Bias: We attribute good results to ourselves, but blame poor results on others or on external circumstances. For product managers, it’s often easier to explain lack of success with “bad design” or “insufficient marketing” rather than flawed assumptions about customer needs.

All three biases reinforce the tendency to keep a product alive longer than is rationally justifiable.

Organizational dynamics

Beyond internal factors, there are external conditions that make it harder for product managers to pull the plug on a product. For example:

No HR Plan B: Let’s be honest: companies rarely have a ready Plan B for employees when a role disappears. Which triggers the fear for one’s career. To be fair, creating such plans would be disproportionately complex and often outdated the moment they are written.

Internal politics: The power and influence of leaders often depends on the number of employees or products under their remit. This gives them little incentive to support a decision to sunset a product early.

Stereotypes: Companies like to celebrate the “go-getter” who fights through resistance and makes their product a success. By contrast, those raising concerns are rarely appreciated. If their product fails, the narrative quickly shifts to blaming their motivation or skills.

In such an environment, few leaders will benefit from supporting an early sunset decision.

Complexity of the decision

Finally, it must be acknowledged that the decision to discontinue a product is genuinely complex. Countless data points need to be collected and analyzed, and products are often interdependent. This is not a decision one can make on the side.

As a result, it rarely fits into the hectic daily business and is often postponed – even though it is one of the most important strategic choices to make.

Why should I as a product manager even care?

We’ve seen that the decision is tough, can impact one’s own career and that of the team, and is rarely appreciated by the organization.

So why should a product manager even bother with this question?

Because there is one central truth:

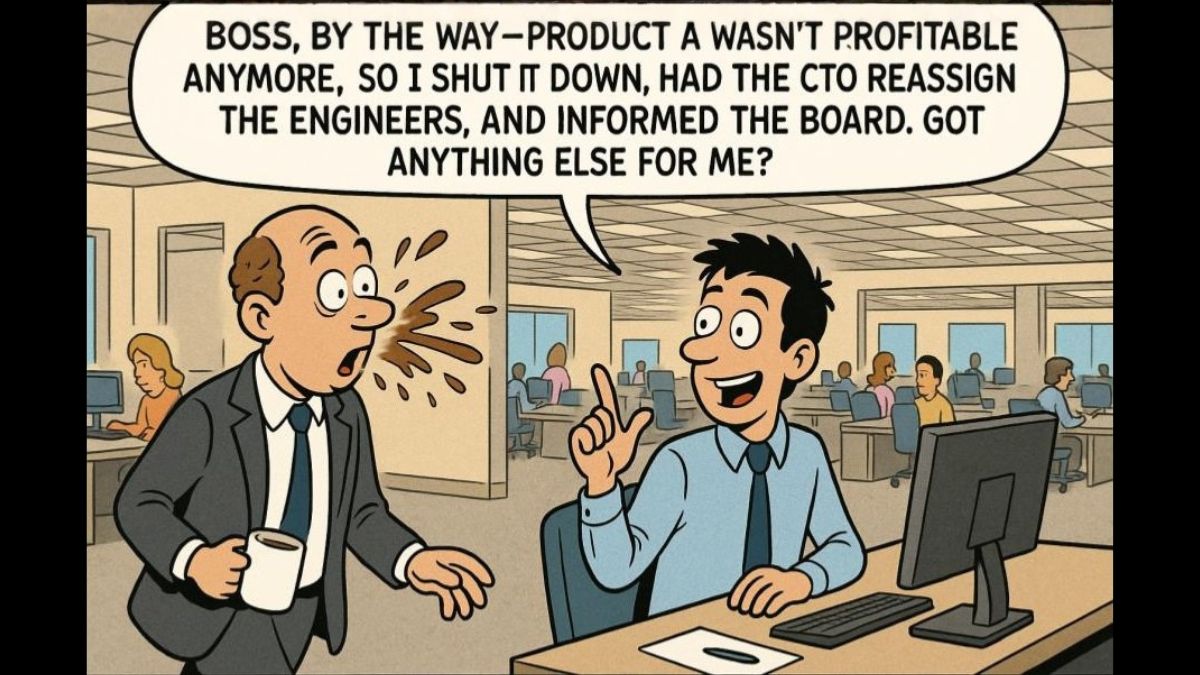

You want to be the one who asks the question first.

As painful as it may be, those who act proactively remain in control. They show themselves to be solution-oriented and dedicated to the success of the company. If the question comes from elsewhere (say, a new C-level executive restructuring the company), the product manager is immediately on the defensive. And if they then respond emotionally, they are quickly seen as resisting change, even if they are right.

So: Be the master of your own fate.

What is needed to make such a decision?

In my view, two things are required:

- The right mindset

- A structured process

The right mindset

It’s crucial to realize that sunsetting a product is part of every product’s lifecycle. Our role as product managers is to manage this phase responsibly, too. Ending a product is not failure – it is responsible action.

Looking at other successful companies helps put this into perspective. Google and Microsoft each have entire “graveyards” of discontinued products, shut down for various reasons. And yet, both companies continue to thrive. Intentional sunsetting is simply part of professional product management.

A structured process

I recommend asking yourself at least once a year whether your product is approaching the end of its lifecycle. The following areas should be examined:

Product data analysis

Gather and organize all relevant product data. In theory, product managers have all key KPIs at hand (ARR, CLTV, CAC, churn, conversion, etc.). In practice, it’s often harder to assemble everything. Moreover, we tend to look at data with an optimization mindset rather than asking: “Is this product still worth the investment?” Additional data may need to be collected to answer that specific question. The application of the product lifecycle model can help here, for example.

Market analysis

Check the state of the market: is it growing or shrinking? How far behind competitors is your product? Classic product management tools such as the BCG Matrix can be useful here.

Dependencies

Examine the interdependencies within the company’s product portfolio. A product may not need to be profitable if it acts as a pipeline or enabler for other profitable offerings.

Standard software

Consider whether the product could be replaced by standard software. Today, there are many robust, proven solutions across domains – from e-commerce to ticketing to dating platforms.

Formulate a recommendation

The analysis should yield an overall picture. It doesn’t need to be a final decision, but at least a fact-based, transparent recommendation. With this in hand, you can start conversations with stakeholders across the organization.

Involving your manager

If you come to the conclusion that the end of the product is near, the next step is to involve your manager. This conversation requires sensitivity: often, concerns about a potential loss of influence or status arise before the business benefits of a sunset decision become clear.

If you can reach a shared conclusion, that decision marks the starting point for the actual product phase-out process.

A few of the scarce resources that outline further steps can be found here.

Practical tips for the process

- I recommend the Amazon Six Pager as a format. Writing forces you to surface your own hypotheses and test them against data. It also produces a document of sufficient quality to involve leadership in the discussion.

- While a PM can go through this process alone, it’s usually beneficial to involve at least part of the team. But be aware: doing so will trigger the same fears and biases among team members. Approach the topic with empathy. Sharing this very blog post might be a useful starting point.

Conclusion

Shutting down a software product is not a personal failure. On the contrary, regularly evaluating whether a product should continue is a sign of seniority in product management.